Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi by Geoff Dyer****

Reading dates: 10 July – 24 August 2025

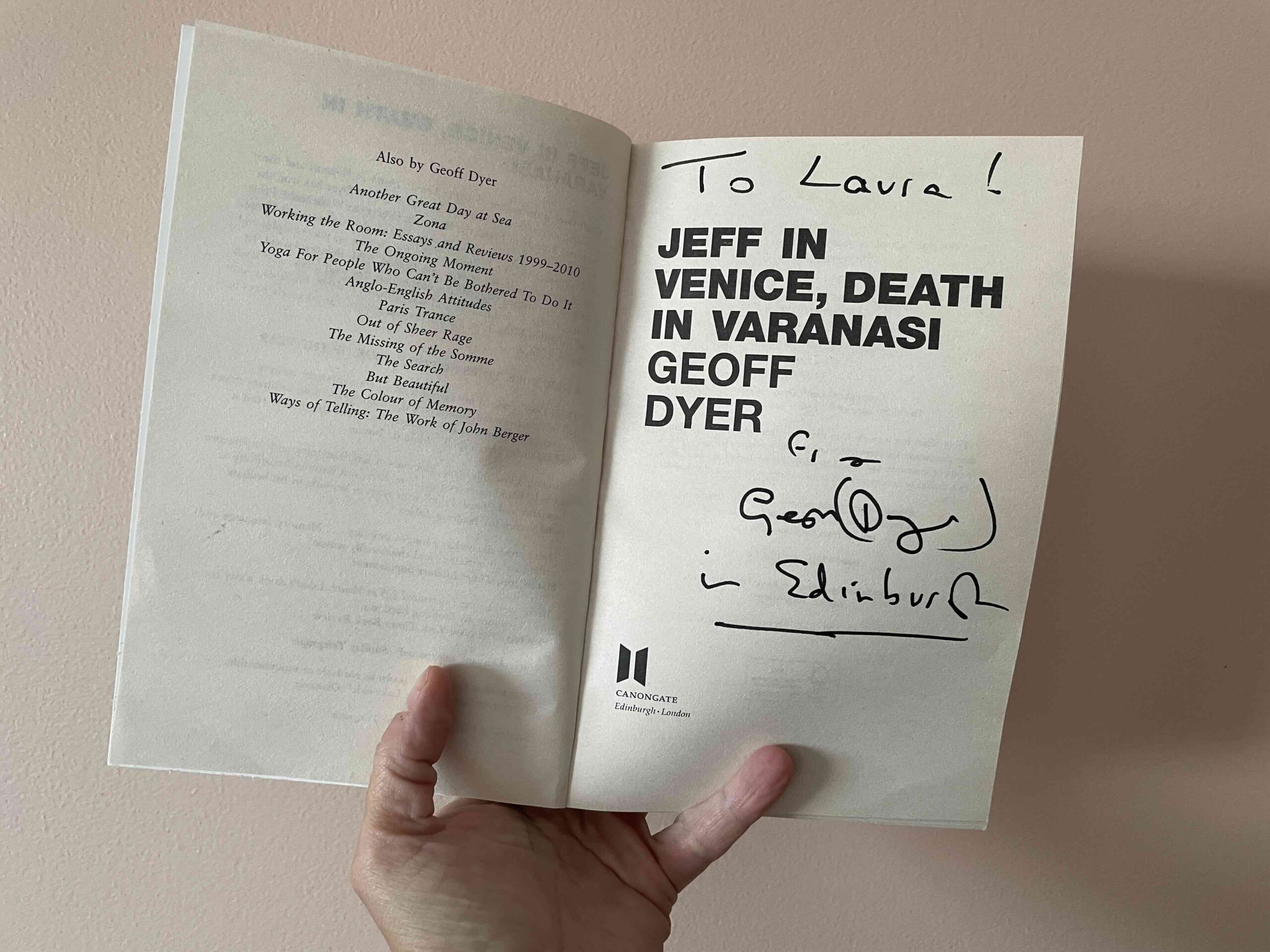

In June, and as part of Neil’s birthday celebrations, we went to Edinburgh to see Geoff Dyer speak about his new book Homecoming. Neil bought a copy but I decided to purchase one of the many books whose title caught my attention: I had been to the Venice Biennale vernissage described in the book, I always wanted to go to Varanasi and my name is Laura. When I asked him to sign my book and mentioned this, his eyebrows rose a fraction more than mere surprise. Maybe that’s why I also got an exclamation mark. He was a very charming man of youthful looks, sharp intellect and a Freitag bag. I liked him.

Any introduction to Dyer always starts with the fact that his books can be found in so many different sections of a bookstore. Another reason to like him. Why conform to genre? Jeff in Venice is purported to be a novel but could equally be in the travel section.

It is an odd book in so many ways: from the structure in two sections (obviously Venice and Varanasi) without chapters to the lack of connection between the two parts. It seems to be indebted to Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, which I have not read. When I chose this off Dyer’s back catalogue (over Yoga for people who can’t be bothered), a few of the Geoff-heads present mentioned I had made an excellent choice. This was ‘a good-one’.

It took me a while to see this. At first, it was ‘a funny-one’. Then, ‘a raunchy-one’, inconveniently discovered on a crowded train to London. But then in Varanasi, something shifted.

For someone which genre-defying hopes for her writing, I was expecting something specific of this book. Perhaps, I also expect something specific of awakening, holding on to an idea firmly attached. Dyer broke it. Unspectacularly too. I liked that, and the fact that I still badly want to go to Vanarasi. He warned me I will be sick.

It was ‘a good-one’, after all. Maybe I think that because Jeff in Venice is written for me in many ways. I could have annotated (and perhaps I will), every single page with comments. It unites my artist and my yogini selves, from a distance offering a blueprint but not a model. A little like Adrian Piper’s Wikipedia page, a compass to direct me in the integration I crave and eludes me.

She rummaged in her bag – a Freitag bag, mainly red.

‘I love your bag,’ he said.

‘Me too. You know what I most love about it?’

‘Let me look.’ He looked at it while she rummaged, even peeked inside slightly. ‘The fact that it’s got a zip,’ he said. ‘Without the zip, its beauty would be diminished by its lack of practicality.’

‘Very good.’

‘Did you think I’d just say “red” or something?’

When he was seventeen he’d read The French Lieutenant’s Woman and had been much impressed by John Fowles’s distinction between the Victorian point of view – I can’t have this forever, therefore I’m miserable – and the modern, existential outlook: I have this for the moment, therefore I’m happy. It had stayed with him ever since but it seemed absurd, now, to have any pretensions to existential contentment. In 2003, in his mid-forties, he had got in touch with his inner Victorian. In Venice he discovered that he was the last Victorian.

The thing about destiny is that it can so nearly not happen and, even when it does, rarely looks like what it is.

Varanasi, it had never fallen into ruin – and never would. Even if every building in it collapsed, it would not be a ruin. The sky was holiday blue. Banners fluttered in the breeze. There was uncomprehended meaning everywhere […]

darshan: the act of divine seeing, of revelation. This was what Hindus went to the temple for: to see their god, to have him or her revealed to them. The more attention paid to a god, the more it was looked at, the greater its power, the more easily it could be seen. You went to see your god and, in doing so, you contributed to its visibility; the aura emanating from it derived in part from the power bestowed on it.

Even if I didn’t know what I was looking at, I could still see.

The fact that the far bank was deserted made it easy to believe that the journey was more than a physical one. The reason the far bank was empty, a young boy with an old face explained, was that if you died over there you would be reborn as a donkey.

It was nothing, just a bit of chat. But it was the first conversation of its kind that I’d had in ages, the first time I’d been able to talk with someone who had an instinctive understanding of another kind of maths that people often find difficult to grasp: that it’s possible to be a hundred per cent sincere and a hundred per cent ironic at the same time. This was the kind of conversation I could feel at home with.

It is strange when two people fancy one another, when liking turns into reciprocated desire: it is tangible. You can see and feel it as a physical force, a kind of gravity.

His face was free of desire. How had he got there? How had he managed that? Did he just happen to be that way? Unlikely. More likely it was a state he had acquired, worked his way towards through meditation, yoga, smoking charas or what-have-you. It seemed a great state to be in, to attain. But for the idea of desirelessness to take root, to set off in that direction, to try to free yourself of desire, surely that must manifest itself as a desire, a yearning, an urge. How, then, does desire transcend itself?

Nothing is stranger, more delicate, than the relationship between two people who know each other only by sight – and nothing is more awkward than the transition from looking to speaking, when words finally come into play.

‘My old self refuses to die. The new is struggling to be reborn. In this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.’